Ancient leprosy strain found in Chile

Ancient Leprosy Strain Found in Chile Sparks Rethink of Disease’s American Origins

In a stunning breakthrough that is reshaping our understanding of disease history in the Americas, scientists have discovered traces of an ancient leprosy causing bacterium in human remains uncovered in northern Chile. The find genetic evidence of a prehistoric strain of Mycobacterium lepromatosis suggests that leprosy may have existed in the Americas thousands of years earlier than previously believed. This revelation is not only rewriting medical history, but it is also raising questions about how the disease may have spread through ancient populations before European contact.

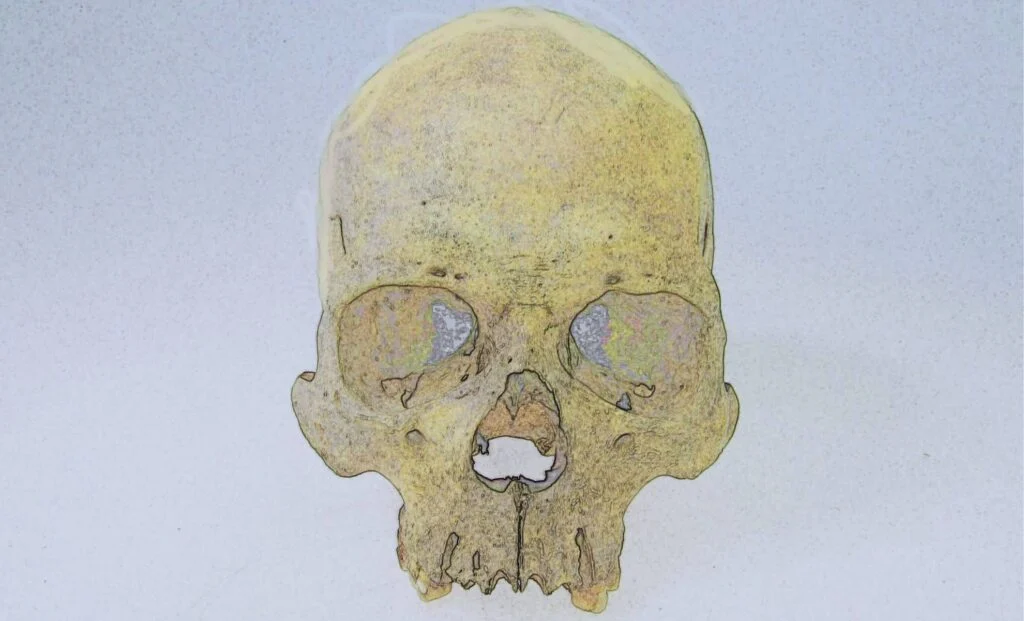

The remains, discovered at a coastal archaeological site believed to be around 4,000 years old, belonged to a member of a pre Columbian Indigenous group that inhabited the region long before the Incan Empire and European colonization. The skeletal remains showed physical evidence of bone erosion consistent with leprosy, prompting researchers to extract DNA from the affected areas. To their surprise, the genetic material revealed a clear match with M. lepromatosis, a strain of leprosy previously believed to have emerged much later in history and found predominantly in modern day Mexico and parts of Central America.

What makes this discovery even more extraordinary is that it challenges the long standing assumption that leprosy arrived in the Americas with European explorers and settlers, particularly during the 15th and 16th centuries. For decades, historians and epidemiologists believed that leprosy was unknown in the Western Hemisphere before the Age of Discovery. However, the presence of an ancient and genetically distinct strain in Chilean remains suggests that the disease may have been circulating among Indigenous populations for millennia. This also raises the possibility that multiple, independent introductions of leprosy occurred across different continents over time.

According to lead researchers from the South American Paleogenomics Consortium, the ancient strain found in Chile shares characteristics with modern M. lepromatosis, yet also contains unique genetic markers indicating long term evolution within the Americas. These markers suggest that the bacterium may have adapted specifically to the human hosts and environmental conditions of prehistoric South America. Unlike Mycobacterium leprae, which has been extensively studied and associated with the classical form of Hansen’s disease, M. lepromatosis is rarer and less understood, making this find all the more valuable.

From a scientific perspective, the DNA analysis was no easy feat. The arid yet saline conditions of the Chilean coast helped preserve the remains, but ancient DNA is notoriously fragile and susceptible to contamination. To ensure accuracy, the team used next generation sequencing methods and ultra clean lab protocols to extract and reconstruct the microbial genome. The results, cross referenced with global pathogen databases, confirmed that this was the oldest known example of M. lepromatosis and among the oldest confirmed cases of leprosy on Earth.

This discovery opens the door to a new understanding of how diseases evolved alongside human migration patterns. If leprosy was present in South America over 4,000 years ago, it implies that the disease could have traveled via early trans Pacific or trans Beringian migration routes or evolved independently on the continent. Either scenario has profound implications. It suggests that ancient trade networks, population movements, and environmental pressures played a much more complex role in disease transmission than previously recognized.

Beyond its scientific impact, this finding carries cultural and ethical weight. Leprosy has long been associated with social stigma and historical isolation of affected individuals. Knowing that Indigenous South American populations may have dealt with this disease thousands of years ago provides a new lens through which to view their medical knowledge, healing practices, and resilience. Some anthropologists believe that traditional treatments many of which are lost to history may have helped these communities manage symptoms and care for those affected in ways not fully understood by modern medicine.

Looking forward, the research team aims to examine additional skeletal remains across other pre Columbian archaeological sites in South and Central America to determine if this strain, or others like it, were widespread. The broader scientific community is also taking notice. Epidemiologists believe that understanding how ancient leprosy strains behaved could help inform modern public health strategies, particularly in regions where the disease still exists in low endemic levels. As more discoveries like this come to light, we may find that the history of infectious disease is far older, more complex, and more deeply tied to the human experience than anyone previously imagined.